Breaking The Sound Barrier

Music, Poetry, and Nonsense in the Modernist Avant-Garde

by Jaren Feeley

What lies between poetry and sound? This essay searches for answers in the dawn the modernist avant-garde, a time when artistic manifestos were hot off the presses and the distinctions between language and noise were being widely challenged.

These are the years before World War I. Avant-garde artists, in step with the profound transformation of societies, were re-inventing forms such as literature, music, painting, theatre, and architecture. New forms such as radio and film were developing. The innovations in these fields were happening rapidly and concurrently, and networks of artists were sharing their ideas. It seemed to be taken for granted by these creative cohorts that their concerns could guide the direction of civilization, for better or for worse. I’ll be focusing in on a few particularly vibrant threads of this rich tapestry: the re-conception of music, poetry, and sound that propelled members of the Futurist and Dada movements, and how these ideas came to fruition through an interdisciplinary approach to art. My hope is to link these avant-garde creations to our contemporary human challenges.

Lets begin the story in 1909 Italy, with the publication of The Futurist Manifesto by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

Marinetti was a charismatic poet, and the founder and chief of Futurism, an artistic and social movement that burst onto the scene in February 1909 with the provocative Futurist Manifesto. Appearing on the front page of major Italian and Parisian newspapers (a true coup), the manifesto articulated a new artistic philosophy that rejected the past and glorified speed, machinery, war, industry, and the radical rejuvenation of Italian culture. The manifesto was extremely abrasive and contained misogyny that makes the contemporary reader wince. It asked for the youth to burn the libraries and flood the museums – and those weren’t even the most extreme demands in the manifesto. Despite its shortcomings, Marinetti’s manifesto had a notable impact on contemporary artists, inspiring wide debate on to what extent art should be mirroring the rapid changes facing an industrializing Europe.

In 1912, Marinetti was hired by a newspaper to cover the Battle of Adrianople, in present day Turkey. Inspired by the cacophony of war he began to write what is arguably his most influential work, Zang Tumb Tumb. Exemplifying his literary philosophy of parole in libertà (words in freedom), Zang Tumb Tumb was groundbreaking in its highly graphic design, and its wild onomatopoetic use of language. Marinetti took the poem on tour around Europe, demonstrating how language could come to embody the radical new soundscapes of industrialized society and war. In 1914, a London newspaper published a review describing a performance of Zang Tumb Tumb: “Listen to Marinetti's recitations of one of his battle scenes - a train of wounded stopped by the enemy, or the destruction of a bridge… I have never conceived such descriptions as these, nor heard such recitations. The noise, the confusion… all were recalled by that amazing succession of words, performed or enacted by the poet”. Relying heavily on onomatopoeia to achieve his sonic effects, Marinetti was harnessing the intense impact of new technology and urban soundscapes to push poetry in a new direction.

The sonic sensitivity of Marinetti was already apparent in his Manifesto, which declares, “We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure and revolt; the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals… and the gliding flight of aeroplanes whose propeller sounds like the flapping of a flag and the applause of enthusiastic crowds.” It was Marinett’s hope that this aesthetic was to be addressed by Futurist composers.

One such contemporary composer, Francesco Balilla Pratella, published a Manifesto of Futurist Music in October 1910. Pratella had overlapping aesthetic concerns with other artists in the Futurist camp, and wasn’t necessarily on the same page as Marinetti in linking music to the sounds of machines. Pratella ostensibly wrote that music should “express the musical soul of crowds, of the great industrial shipyards, the trains, the transatlantics, battle ships, cars and airplanes.” But in a humorous example of the the pressures faced by revolutionary artists to conform to their camps, Pratella later admitted that the comments establishing a “rapport between music and machines… were neither written nor even thought by me and often are in contrast to the rest of the ideas. These inventions were added by Marinetti… I was astonished to read them over my signature”.

In the end, it was a young obscure Futurist painter by the name of Luigi Russolo, who, inspired by Marinetti’s liberation of sounds from syntax and grammar, assimilated the sounds of the modern world and the craft of music.

The Art of Noises (Italian: L'arte dei Rumori) was a manifesto published by Russolo in 1913, and is widely considered a seminal text of 20th century musical aesthetics, predicting and perhaps influencing developments in musique concrète, and the work of major composers such as Edgard Varèse and John Cage. The manifesto went beyond mere theories of music, addressing the sensory system and connecting it to the development of technology and society. “Noise was really not born before the 19th century, with the advent of machinery. Today noise reigns supreme over human sensibility,” Russolo begins. He appeals to the reader:

Let’s walk together through a great modern capital, with the ear more attentive than the eye, and we will vary the pleasures of our sensibilities by distinguishing among the gurglings of water, air and gas inside metallic pipes, the bumblings and rattlings of engines breathing… the rising and falling of pistons, the stridency of mechanical saws, the loud jumping of trolleys on their rails.

In his book The Audible Past, Jonathon Sterne argues that to imagine “the possibilities of social, cultural, and historical change—in the past, present, or future—it is also our task to imagine histories of the senses”. What our senses are attuned to changes over time, which leads us to understand our society and environment in new ways. Thus as our societies develop, there is a dynamic interplay between the ways we change the world, and the ways these changes can affect our sensory experiences. The aesthetic manifestos that were so prevalent at the turn of the 20th century (such as The Art of Noises) functioned upon this malleability of the public’s sensibilities. The rousing rhetoric of the manifestos urged the reader to experience the world in a different way, they sought a transformation in the process of sensory experience; for if the process of sensory input were altered, information channeled through those sense organs would be altered by consequence.

Russolo combines a keen sonic sensitivity with a desire to craft raw noise-sounds into music: “…musical sound is too restricted in the variety and quality of its tones… this is why we get infinitely more pleasure imagining combinations of the sounds of trolleys, autos and other vehicles, and loud crowds”. Significantly, Russolo argues “…the art of noises must not be limited to mere imitative reproduction. The art of noises will extract its main emotive power from the special acoustic pleasure that the inspired artist will obtain in combining noise”. Russolo goes no further in elaborating on what this “special acoustic pleasure” entails, but his lack of detail suggests this entails a continuation of the traditional harmonic ideas. There are nuances that Russolo recognizes in using noises as musical material—namely, the presence of many dissonant simultaneous tones and irregular rhythms, all of varying amplitude. Creating traditional harmonic patterns out of such multifaceted and inherently dissonant musical material seems to be the goal of Russolo:

We want to score and regulate harmonically and rhythmically these most varied noises. Not that we want to destroy the movements and irregular vibrations (of tempo and intensity) of these noises! We wish simply to fix the degree or pitch of the predominant vibration, as noise differs from other sound in its irregular and confused vibrations.

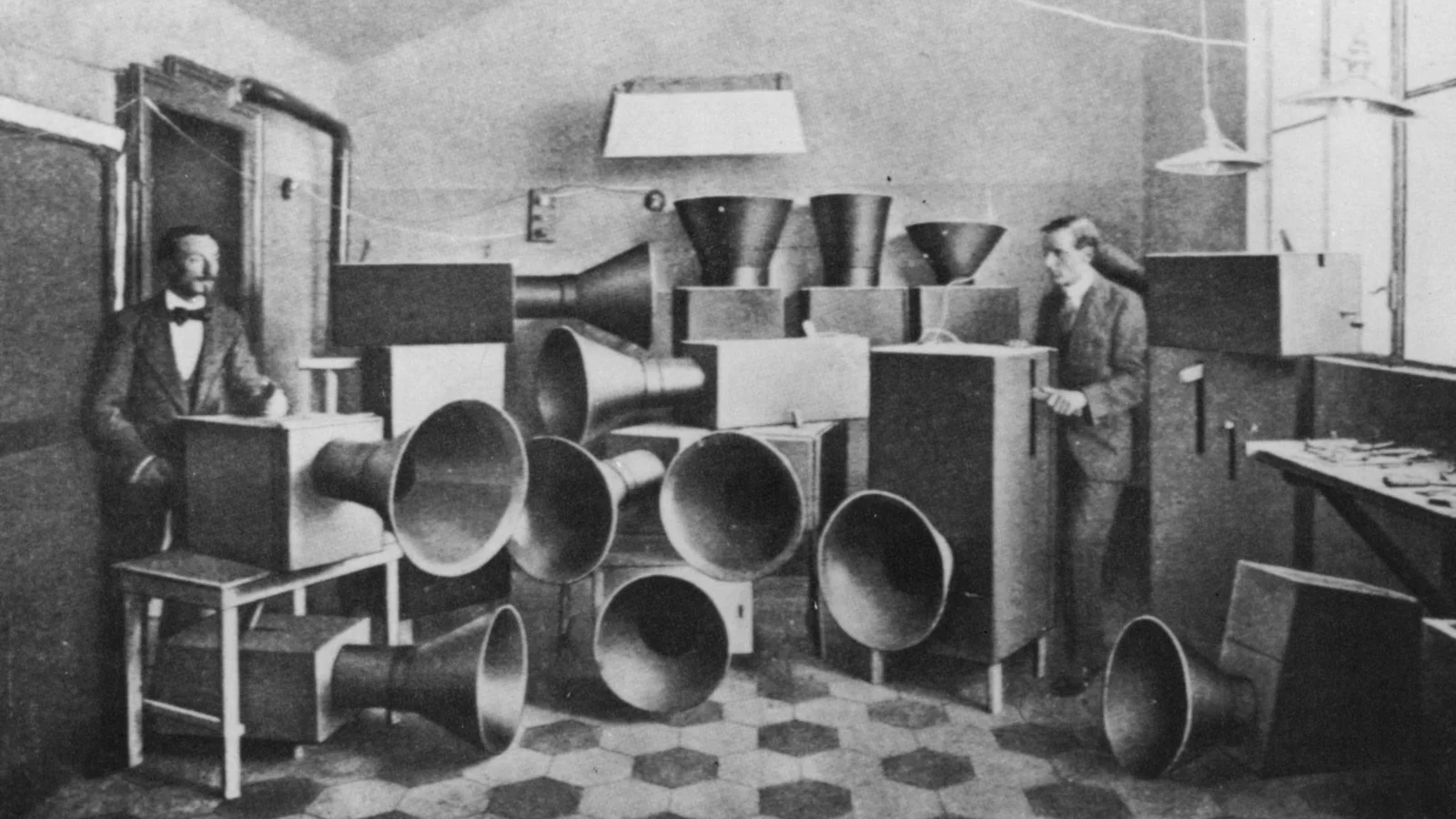

The expansion of timbral possibilities in music has been considered the most innovative aspect of Russolo’s aesthetic musings. However, Russolo was also noteworthy in his eschewing of the limitations of the 12-semitone scale. He “rejected any division of the sonic spectrum into discrete pitches… he argued, the tempered harmonic system is analogous to a system of painting that would accept only the seven colors of the spectrum”. After publishing his manifesto, Russolo immediately set upon building his own noise instruments, intonarumori, which could assume the sounds of the city and environment while having enough precision to operate as a melodic musical instrument. Russolo improved upon his noise instruments, eventually developing the rumorarmonio, which controlled “all the timbres of the individual intonarumori and controlled them through a keyboard interface”, a remarkable mechanical prototype of the electronic synthesizer. Across the Atlantic around the same time, a man named Arthur Nichols was building an complex instrument that could play multiple types of timbral effects using a single interface, but this invention is generally not mentioned in the literature as it was used to provide theatrical sounds in radio rather than being used as an instrument in its own right. Russolo on the other hand built a small orchestra of these intonarumori, as he called his noise-instruments, and he promptly took them on a concert tour around Europe.

The avant-garde community took notice of Russolo and his strange instruments. Many were critical, such as Ezra Pound: the “the general vorticist stand,” according to Pound, was that

“new vorticist music would come from a new computation of the mathematics of harmony not from mimetic representation of dead cats in a fog horn (alias noise tuners).”

Others quickly took to imitating the aesthetic Russolo pioneered. In 1917, Erik Satie collaborated with Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso to create a ballet called Parade. Caroline Potter writes of Satie incorporating “ ‘found sounds’ such as the typewriter, the revolver and sirens. These ‘found sounds’ probably originated at Cocteau’s suggestion. What Satie did in the final score was not simply to employ these sounds or noises as part of the musical soundscape; they are musical sound. They are closer to what the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo claimed was necessary in his 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises.” Parade also features another notable marker in the history of the modernist avant-garde: Guillaume Apollinaire wrote in the first program notes for “Parade” that the piece exhibited “a kind of surrealism”, thus coining the term that would come to describe another major artistic movement soon to come.

The experimental sonics of Russolo, originally inspired by the prose of Marinetti, would soon turn back again to the realm of language.

The poets of the fledgling Dada movement at Cabernet Voltaire in Zurich took note of Russolo’s new aesthetics (which they termed ‘Bruitism’), and incorporated it into their poetry—thus taking the form sonically and conceptually further than Marinetti did originally when he inspired Russolo. In this way, the experimental practice of sound poetry was able to progress through a transfer of knowledge and inspiration from poets to musical composers and then back again.

Dada poet and drummer Richard Huelsenbeck wrote in 1920: “[Dadaism] disseminated the BRUITIST music of the futurists… noise with imitative effect was introduced into art (in this connection we can hardly speak of individual arts, music or literature)”. Russolo had disdained the division of the sonic spectrum into discrete pitches, and had sought to unleash the full spectrum of sonic experience at the expense of the former music syntax—and now Dadaists were doing the same to the voice and its conceptual and phonetic bounds of language.

One of the leaders of Dada in Zurich was Hugo Ball, a German author and poet, who would write the Dada Manifesto in 1916. In October 1913, Ball attended an exhibition of futurist paintings and had a visceral response to the way the Futurists represented the modern mechanistic zeitgeist. It was “a representation he applauded for its truthfulness but abhorred for its content… with the outbreak of war his conviction of the need for a new spiritualism deepened. His writing denounced rationality and the machine as being responsible for the destruction of Europe”. Ball traveled to Belgium to witness the war. Horrified at what he saw, Ball fled to Zurich, where he helped found Dada and its cultural epicenter, Caberet Voltaire.

Members of Dada, many of them refugees, had heaped criticism not only on the current war, but also on the linguistic framework of contemporary European institutions – the church, legal and political systems – that created in their eyes a ‘grammar of war’. Contemporary writer Steve McAffery astutely notes that this line of thinking anticipates Foucault’s widely heralded work on discourse and the critique of language.

It is in Zurich on June 23rd that Hugo Ball performed the first of his famous Verse ohne Worte (poems without words). He made himself a Cubist-inspired costume, and was carried onto the stage in the dark, reciting solemnly:

Gdji beri bimba

Glandridi lauli lonni cadori

Gadjama bim beri glassala

Glandridi glassala tuffm I zimbrabim

Blassa galassasa tuffm I zimbrabim

Ball writes in his journal after the night of his first performance:

In these phonetic poems we must totally renounce the language that journalism has abused and corrupted. We must return to the innermost alchemy of the word, we must even give up the word too, to keep for poetry its last and holiest refuge. We must give up… words (to say nothing of sentences) that are not newly invented for our own use.

In reimagining the unappreciated, the “noise” and the “bruit”, the Futurists and the Dadaists reconceived how we can sense and interact with the world. In order to progress into the unknown and gain a good glimpse of what is possible, they suggest that merely paper walls between disciplines often must be overcome. Poetry, music, and sound continued to synthesize and morph into new forms throughout the 20th century, through avant-garde poets and composers such as Robert Desnos (“Description of a Dream”), Pierre Schaeffer (music concrète), William S. Burroughs (the cut-up technique), John Cage (“Empty Words”), and the Star Wars Ewok people (the forest moon of Endor, where they speak a recorded and manipulated amalgamation of three human languages and nonsense words).

In the 21st century, aided by a century of advances in audio electronics (in no small part due to military research in the world wars) the art of noises has been developed to an astonishing degree, something that was not in the cards for sound poetry. Still, the synergy between music, language and sound is not likely to end, a most recent example being a “Globalalia”, composed by Trevor Wishart, created using 8,300 sound sources of language, broken up into phonetic chunks that are then transmogrified into music. Paul Hegarty, in the anthology Sound, Music, Affect, suggests that “noise must be heard in relation to not-noise: to harmony, structured music, meaning, language, discourse…This means that noise is historical and social, and that what is noise at a given moment will not necessarily always be noise”. In this way, the art of noise is always elusive, it is always that thing of beauty unrecognized and unappreciated, waiting to be discovered.

Sources

Belloli, Carlo. "Filippo Tommaso Marinetti." MoMA.org. Oxford University Press, 2009. Web. 16 May 2014.

Chessa, Luciano. Luigi Russolo, Futurist: Noise, Visual Arts, and the Occult. Berkeley: U of California, 2012. Print.

Cox, Cristoph. "Music, Noise, and Abstraction." Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art. Ed. Leah Dickerman and Matthew Affron. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012. Print.

Elderfield, John. Preface. Flight out of Time: A Dada Diary. By Hugo Ball. New York: Viking, 1974. Print.

Graham, Clive. 'Sound Poets Exposed' The Story of a Radio Programme. Playing with Words: The Spoken Word in Artistic Practice. Ed. Cathy Lane. London: CRiSAP (Creative Research into Sound Arts Practice), London College of Communication, 2008. Print.

Hegarty, Paul. Brace and Embrace: Masochism in Noise Performance. Ed. Ian D. Biddle. Ed. Marie Thompson. Sound, Music, Affect: Theorizing Sonic Experience. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. Print.

Kahn, Douglas. Noise of the Avant-Garde. The Sound Studies Reader. Ed. Jonathan Sterne. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Lane, Cathy, and Trevor Wishart. Trevor Wishart Interviewed by Cathy Lane. Ed. Cathy Lane. Playing with Words: The Spoken Word in Artistic Practice. London: CRiSAP (Creative Research into Sound Arts Practice), London College of Communication, 2008. Print.

Marinetti, Filippo T. "Futurist Manifesto" Editorial. Gazzetta Dell'Emilia [Bologna] 5 Feb. 1909. Web. 15 May 2014.

McAffery, Steve. Cacophony, Abstraction, and Potentiality: The Fate of the Dada Sound Poem. Ed. Marjorie Perloff. Ed. Craig Douglas. The Sound of Poetry/the Poetry of Sound. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2009. Print.

Nice, James. "F.T. Marinetti: La Battaglia Di Adrianopoli." A Young Person's Guide To The Avant-Garde [LTMCD 2488] Various Artists. LTM Recordings. Web. 16 May 2014.

Orban, Clara Elizabeth. The Culture of Fragments: Word and Images in Futurism and Surrealism. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997. Print.

Orledge, Robert. Satie the Composer. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. Print.

Ovadija, Mladen. Dramaturgy of Sound in the Vant-garde and Postdramatic Theatre. Montreal: McGill-Queen's UP, 2013. Google Books. Web. 16 May 2014.

Potter, Caroline. Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature. Ashgate, 2013. Google Books. Web. 16 May 2014.

Pound, Ezra, and R. Murray, Schafer. Ezra Pound and Music: The Complete Criticism. New York: New Directions Pub., 1977. Print.

Russolo, Luigi. The Art of Noise. UBU Classics, 2004. Print.

Sterling, Christopher H., Cary O'Dell, and Michael C. Keith. The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Sueoka, Dawn. "Hidden Harmonies in John Cage's 'Empty Words'" Jacket2. 29 Aug. 2012. Web. 16 May 2014.

Venn, Edward. "Rethinking Russolo." Tempo 64.251 (2010): 8. Web.