Love's Goodness

Literature and Philosophy - An Exploration

by Jaren Feeley

A prevailing view sees ethics as the domain of the philosophical method, where the cold steel of rationality can properly pare away emotion, attachment, and contradiction—laying bare the essential aspects of our moral dilemmas and providing us with abstract principles for guidance. This view commonly considers literature unnecessary for thorough ethical reflection; literature being at best “an orchard full of juicy examples”,[1] at worst a misleading art which subverts rational deliberation through appeal to emotion.[2] Martha Nussbaum, in her books Love’s Knowledge and The Fragility of Goodness, challenges this view, arguing that well-written literature aids our efforts to live an ethical life in ways that prosaic philosophy cannot.

This essay will critically explore Nussbaum’s wide net of claims for the ethical eminence of literature. As I find the bulk of Nussbaum’s arguments cogent and compelling, I will pay particular attention to those aspects of her work that strike me as problematic, in particular: 1) the Aristotelian methodology upon which her work is built, 2) her discussion of how an ethical conception can be emphasized through the resonance of style and form, and 3) the implications of her claims that literature and philosophy should be partners in the practical search for a good life.

[1] Jane Adamson, 'Against Tidiness: Literature and/versus moral philosophy', in Renegotiating Ethics in Literature, Philosophy, and Theory, ed. by Jane Adamson, Richard Freadman, David Parker (Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 84-110 (p. 89).

[2] Charles L. Griswold, "Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/plato-rhetoric/>.

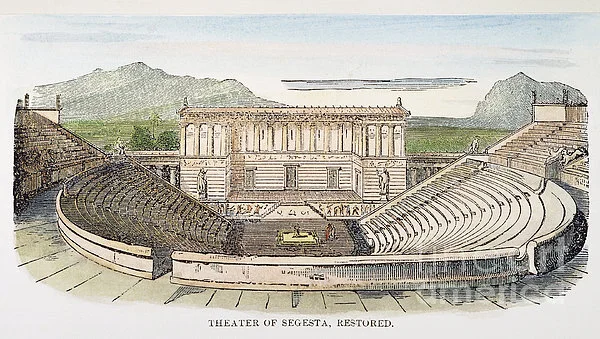

Nussbaum’s interest in the ethical relevance of literature begins with her engagement with Greek tragedy, which ascribe ethical importance to fortune, conflicting obligations, and especially the emotions and passions. She writes that she very rarely found this recognition in the thought of “the admitted philosophers, whether ancient or modern”.[1] The ethical implications of Greek tragedy are examined in her book The Fragility of Goodness. As she deepened her study of philosophy and classical literature, she writes that she began to “sense that there were deep connections between the forms and structures characteristic of tragic poetry and its ability to show what it lucidly did show”.[2] In her next book, Love’s Knowledge, Nussbaum expands this line of thought, arguing that in all well-written works there is an important connection between form and content, and that in the domain of moral philosophy in particular, literary narratives can best express and embody the importance of certain ways of perceiving, thinking, and living an ethical life.[3]

[1] Martha Nussbaum, Love's Knowledge (Oxford Universtiy Press, 1990), p. 14.

[2] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 14.

[3] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 5.

Nussbaum is making a variety of interconnected claims. The first major claim, begun in The Fragility of Goodness, implicates Nussbaum in Plato’s famous “quarrel between philosophy and poetry”[1] (“poetry” here referring to the work of the ancient Greek playwrights), with Nussbaum firmly on the side of the Greek playwrights and in support of the ethical value of their works.[2] We must understand Plato’s influential argument to appreciate Nussbaum’s position. Plato, finding the ancient poet’s account of ethics untenable and their style emotionally manipulative, began the project of creating a different conception of the human good.2 Plato’s took great issue with the idea that virtuous people could be harmed by circumstances outside of their control, and began what Nussbaum calls a “heroic attempt […] to save the lives of human beings by making them immune to luck”.[3] To this end, Plato argued for the value of a self-sufficient activity unaffected by luck or misfortune: philosophical contemplation.8 Emotional responses to the tragic elements of human life are thus a symptom of incorrect ethical outlook.8 Plato’s critique extends beyond the ethical content of the tragic plays, to the style of these works. Plato argues that the truly insidious power of drama is its ability to draw the audience into the emotional state represented by the actors, spellbinding us at the murky level of emotion and irrationality.8 For Plato, our sense of the beautiful is closely tied to our sense of the ethical, and thus through shaping our fantasies and feelings the poets also shape our characters8. Thus, the poets are not only improper arbiters of what is right and good, but through the powers of dramatic representation they are able to gain access to the emotional roots of our mind, their works like beautiful Trojan horses which carry within false conceptions of goodness. Nussbaum writes that Plato, recognizing that the works of the tragic poets were ethical reflections “embodying in both their content and their style a conception of human excellence”,7 created his own style of philosophical discourse, which was “linked with specific views about the good life and the human soul”.[4]

[1] Plato, Republic, 607b5–6.

[2] Martha Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness (Cambridge University Press, 1987), p. 13.

[3] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 8.

[4] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 12.

In The Fragility of Goodness, Nussbaum responds to Plato’s ethical and poetic ideas, arguing for the ethical relevance of these tragic plays, and their stylistic depictions of uncontrolled fortune, conflicting obligations, and passion. The essential question raised by Nussbaum is: to what extent to we let these vulnerabilities into our life, if we aim “to live the life that is best and most valuable for a human being?”[1]

The first step for Nussbaum is establishing her mode of ethical inquiry. In analyzing these tragedies, what will be taken as ethical? What will be taken as truth? Where does our capacity for rationality and intuition fit in our ethical conceptions? How will we respond to conflicting ethical conceptions? Nussbaum’s response to these questions is based in her commitment to an Aristotelian mode of practical ethical inquiry, which aims to answer the fundamental question: “how should we live?”[2] This is achieved through an examination of one’s ethical beliefs and intuitions in critical dialog with a series of diverse and complex ethical conceptions.[3] Assuming that one is well brought up and already has certain attachments and intuitions relating to virtue,[4] one can use this reflective dialog to help intellectually clarify “what they really think”.13 And when, writes Nussbaum:

they have arrived at a harmonious adjustment of their beliefs, both singly and in community with one another, this will be the ethical truth, on the Aristotelian understanding of truth: a truth that is anthropocentric, but not relativistic. (In practice the search is rarely complete or thorough enough; so the resulting view will just be the best current candidate for truth.)[5]

This is a remarkable series of assertions, particularly about the relationship of ethical intuition to truth. It is not hard to see that this starting point ‘stacks the deck’ of our analysis of Greek tragedy, paving the way for an affirmation of its ethical relevance. First, ethics is now a personal and practical mode of inquiry—as opposed to Plato’s conception of an eternal truth available only to an elite cadre of philosophers, or Kant’s universal standard of rationality. Second, we are open to enter into dialog with quite loosely defined “complex ethical conceptions”,13 of which the Greek tragedies could very arguably fit. Third, our intuitions about virtue play a central role (assuming we’ve been properly conditioned), ostensibly allowing us to avoid being manipulated by ethically subversive literature. Nussbaum confirms: “Thus if the enterprise of moral philosophy is understood as we have understood it […] then moral philosophy requires such literary texts”.[6]

[1] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 4.

[2] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 5.

[3] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 10.

[4] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1095b4–6.

[5] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 10-11.

[6] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 26-27.

“There is a deep problem here”,13 Nussbaum writes, awake to the way in which her Aristotelian methodology seems to auto-collect her desired conclusions. In her opening pages of her next work, Love’s Knowledge, the same problem rears its head: “No starting point is altogether neutral here. […] Traditions each embody norms of procedural rationality that are part and parcel of the substantive conclusions they support.”[1] Here we see Nussbaum explicating stating the impossibility of neutral procedures of rationality, a feature that is central to Kantian ethical conceptions, and to much of contemporary philosophy—and as these are precisely the modes of thought which Nussbaum pushes against in her essays, the perception that her methodology strongly reflects her conclusions is deepened. Nussbaum writes: “My commitment to proceed in an Aristotelian way is as deep as any commitment I have; I could not possibly write or teach in another way”,[2] a statement which has resonance with the Aristotelian idea that ethical truth hinges upon those irrevocable beliefs and intuitions which are inculcated in us from a young age. At any rate, Nussbaum does not have much time to dwell on these problems, as she writes that ethics are not a matter of methodological purity, but of our urgent practical need.17

[1] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 28.

[2] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 11.

In the course of The Fragility of Goodness, Nussbaum comes to similar conclusions as Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics. Humans are social animals,[1] and the good life involves engagement with our social milieu,[2] this engagement being driven in large part by our emotions and (often sexual) passions.[3] It follows that in the process of living an ethical life we find ourselves powerfully linked to others.20 However, this connection with others also takes away some of our self-sufficiency, and makes us vulnerable to loss.20 Even if we live with integrity and dedicate ourselves to an ethical life, there are still things outside of our control which may infringe on our flourishing[4]. This is the tragic element of human existence which is so vividly portrayed by the ancient Greek playwrights, and through these portrayals Nussbaum argues that we can better understand this aspect of our life.20

With this foundation, we now come to Love’s Goodness, in which Nussbaum argues that literary narratives can best express and embody the importance of certain ways of perceiving, thinking, and living an ethical life. To back this, Nussbaum points to the connection between form and content in well-written works:

any style makes, itself, a statement: that an abstract theoretical style makes like any other style, a statement about what is important and what is not, about what faculties of the reader are important for knowing and what are not.[5]

Nussbaum stresses that style highlights what is important, implicitly suggesting that philosophical prose is not incapable of expressing in general terms the ideas developed in literature, but rather that literature, through its style, better expresses the importance of certain lines of thought. She continues:

there is a family of positions that is a serious candidate for truth […] whose full, fitting, and (as James would say) ‘honorable’ embodiment is found in the terms characteristic of the novels here investigated. [6]

Once again, Nussbaum stresses that our relationship with literature does not necessarily offer exclusive access to new conceptions, but rather a fuller and qualitatively richer experience of ethical reflection.

[1] Aristotle, Politics, 1253a.

[2] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 21.

[3] Nussbaum, Goodness, p. 6-7.

[4] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1099a31-b9.

[5] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 7.

[6] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 8.

Nussbaum calls particular attention to how stylistic qualities of the text, and especially the way the narrator exemplifies a certain psychological outlook, can reinforce the ethical statements made in the text. She lists some examples:

David Copperfield writes with the kind of attention that he also practices. Seneca leads the interlocutor (and the reader) away from passion even while he condemns it. Spinoza cultivates the intellectual joy of which he will speak. [Henry] James’s text exemplifies, on the whole, a kind of consciousness of which it frequently speaks with praise.[1]

Not all of the above examples are equally compelling, with Spinoza’s cultivation of “intellectual joy” coming across as a stretch, while James’s “on the whole” resonance of narrative consciousness and ethical statement appears to be a more developed interweaving of form and content. Indeed, while Nussbaum’s argument that aspects of style can reinforce (or ironically call attention to) the textual content is convincing, it also seems overstated in service of her focus on literature—such as The Golden Bowl by James—which conveys the subtle emotional psychology of human relationships. The alignment of style and ethical statement comes across as gilding rather than an essential feature.

[1] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 35.

These more essential features of the narrative genre are considered next. If one is in agreement with the Aristotelian ethical conception, this section of Nussbaum’s work is particularly compelling. Nussbaum points to the ethical quality of four main features of the nature genre:

1) “Noncommensurability of the Valuable Things”.[1] The literary artist can richly depict the unique qualities that are held by objects. When we value different things, we may be torn between conflicting desires or obligations, a common situation that can also be well depicted in literature, especially tragedy.

2) “The priority of Perceptions”.[2] In an Aristotelian ethical view, general ethical categories and rules for action are inadequate for confronting the ever-unique stream of situations we find ourselves in. Great emphasis is thus placed on our “ability to discern, acutely and responsively, the salient features of one’s situation”, which will allow us to act appropriately. Narratives not only depict keen perceptiveness in the context of complex of situations, but also through our engagement with the text train us to be more perceptive.

3) “Ethical Value of the Emotions”[3]. Nussbaum argues that emotions, though frequently dismissed as irrational and distracting, actually are useful in alerting us to the state of our beliefs and values, the connection which could be lost if one is engaged in emotionless intellectual reasoning. Nussbaum argues that the vulnerability entailed by engaging emotionally with things external to us is a necessary side effect of living a good, loving life.

4) “Ethical Relevance of Uncontrolled Happenings”[4]. Through literature, we are able to identify with characters and their aspirations to live well, with the way these aspirations can be checked by misfortune.

[1] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 36.

[2] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 37.

[3] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 40.

[4] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 43.

If we follow Nussbaum in holding literature as a significant source of ethical reflection, we still are left with the final question of how literary and philosophical discourse will share in our conception of ethics. If the ethical content of literature is interwoven in its style and structure, then we cannot simply abstract the ethical content from novels into philosophy. Nussbaum writes that it is the

mysterious, various, and complex content [of literature] that we wish to preserve and to bring into philosophy—which means, for us, just the pursuit of truth, and which therefore must become various and mysterious and unsystematic if, and insofar as, the truth is so.[1]

This claim is problematic, as it implies that we need to collapse some of the boundaries between literature and philosophy, and yet Nussbaum does not elucidate further on how this might be carried out. The “unargumentative exploratory moral thinking”[2] exemplified in her choice of novels is in many ways diametrically opposed to the aims of philosophy, which is rational, concise, argumentative and goal oriented.[3] The indissoluble relationship of content and form which Nussbaum has been arguing for would seem to indicate that modes of discourse are even more tightly self-entangled than one would have previously supposed. Attempting to inject imagination and mystery into contemporary analytic philosophy may unravel its identity entirely. Perhaps a more fitting synthesis of her argument would bring us back to our Aristotelian methodology, seeing philosophical and literary modes of thought as those “diverse and complex ethical conceptions”12 with which we could fruitfully engage in dialog.

In this essay, Nussbaum’s arguments for the ethical eminence of literature have been critically explored. Particular attention was given to the to Aristotelian methodology upon which her work is built, her discussion of how style and form can resonate to stress an ethical outlook, and the implications of her claims that literature and philosophy should be partners in the practical search for a good life.

[1] Nussbaum, Knowledge, p. 29.

[2] Adamson, ‘Tidiness’, pp. 84-110 (p. 104).

[3] Adamson, ‘Tidiness’, pp. 84-110 (p. 87).

Bibliography

Adamson, Jane. ‘Against Tidiness: Literature and/versus moral philosophy', in Renegotiating Ethics in Literature, Philosophy, and Theory, ed. by Jane Adamson, Richard Freadman, David Parker (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, ed. by Rodger Crisp, trans. by Rodger Crisp (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Griswold, Charles L., "Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/plato-rhetoric/>.

Kraut, Richard, "Aristotle's Ethics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2014/entries/aristotle-ethics/>.

Nussbaum, Martha. Love's Knowledge. (Oxford: Oxford Universtiy Press, 1990).

Nussbaum, Martha. The Fragility of Goodness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

Plato, The Republic of Plato, ed. by Alan Bloom, trans. by Alan Bloom, 2nd edn (New York: BasicBooks, 1991), p. 290.